How to Choose a Large Language Model (LLM): Why Model Selection Is Harder Than It Looks

Introduction: how to choose a Large Language Model in 2026

Choosing a large language model (LLM) is no longer a simple procurement decision. In 2026, teams building LLM-powered products must choose between dozens of capable models - including GPT-5.2, Claude 4.5, Gemini 3, Llama 4, and Mistral Large 3 - each with different strengths, pricing, latency, reliability, and safety trade-offs.

Benchmarks, vendor claims, and social-media demos rarely reflect production reality. A leaderboard-topping model may hallucinate on your domain data, a great demo may hide unacceptable latency, and a cheaper model may drive up downstream manual review costs. As a result, large language model selection has become a multi-dimensional engineering problem with no single “best” model.

This guide explains why public benchmarks alone are insufficient, why evaluating models on your own data is essential, and how to run a practical, repeatable model-selection process using task-specific metrics, human and LLM-as-a-Judge evaluation, and continuous re-evaluation. At Trismik, we help ML and product teams move beyond vibes-based decisions toward structured, defensible LLM selection that continues to work as models, data, and requirements evolve.

Why LLM selection is harder than most teams expect

Since 2023, the explosion of models and versions has created a landscape that changes monthly. The growing number of LLMs available for selection and deployment means teams must stay updated on the latest advancements and options. Major providers push API updates, release new checkpoints, and cut prices in competitive cycles that make last quarter’s evaluation obsolete. The model you selected in January might be deprecated by June, or silently updated in ways that change its behaviour.

There is no single “best” LLM. Model performance is highly task-dependent. GPT-5.2 may beat others on complex reasoning and code generation, while Claude 4.5 Sonnet wins on long-document analysis with its extended context window. Open models like Llama 3.1 can be dramatically cheaper at scale when you’re running models on your own infrastructure. A model that excels at text generation might underperform on data extraction or classification tasks.

The challenge of non-stationarity compounds this problem. Vendors silently update models, deprecate older versions like GPT-3.5 or Gemini-1.5 model endpoints, and change throttling policies without warning. Your production system might start behaving differently not because you changed anything, but because the underlying model drifted.

Evaluation itself is noisy. Prompt sensitivity, temperature settings, and sampling parameters can change apparent rankings between models. A small prompt tweak might flip which model “wins” on your test set. Comparing multiple models is essential to get a reliable assessment and avoid overfitting to a single configuration. Consider a realistic scenario: your team builds an internal tool for contract summarization. You test three models on fifty contracts. Model A wins. But when you refine your prompt template based on user feedback, Model B suddenly performs better. Without a structured approach to testing LLMs, you’re making decisions based on noise rather than signal.

The hidden trade-offs: cost, quality, latency, and reliability

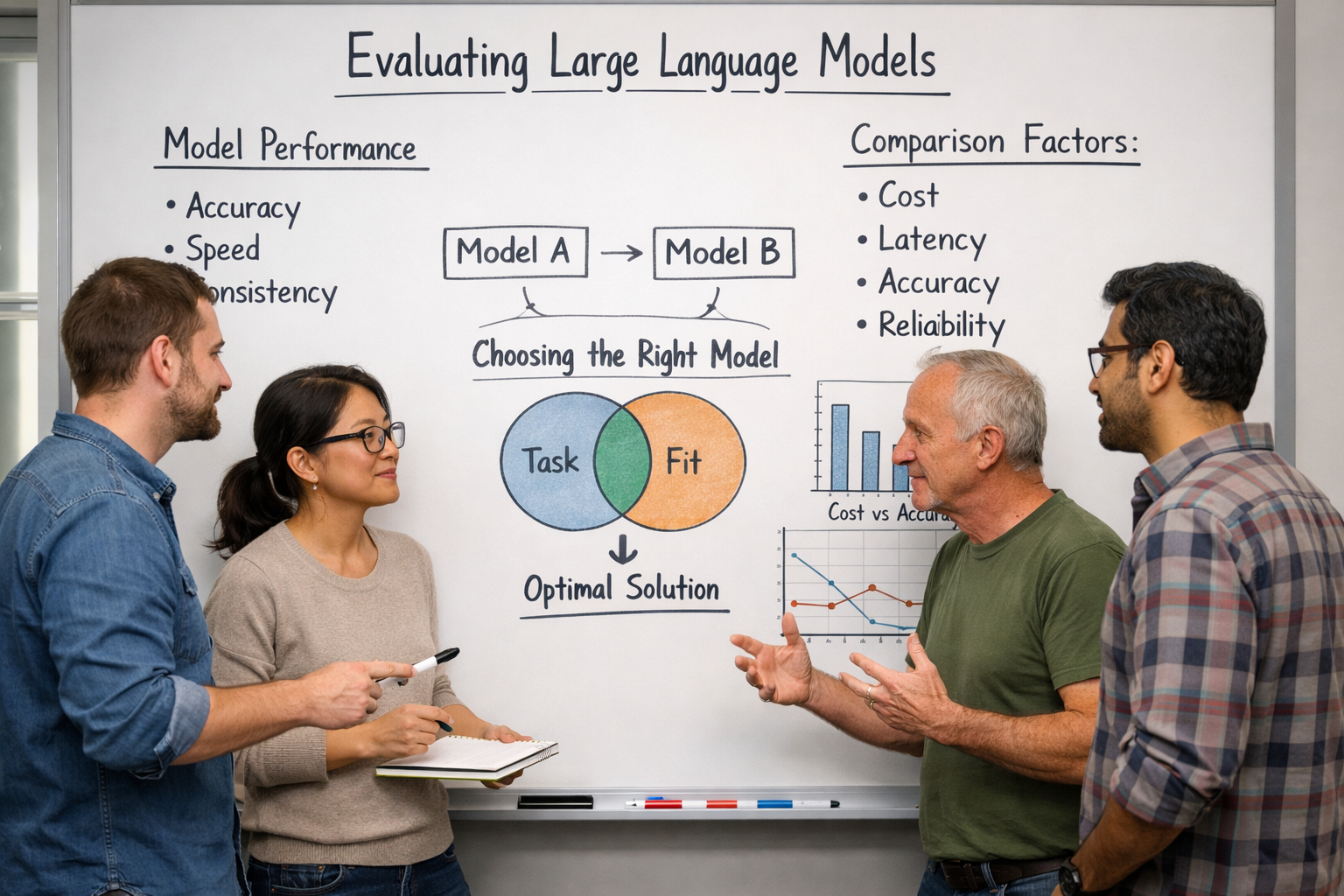

Model selection is fundamentally multi-objective optimization, not a single metric choice. You cannot simply pick “the best model” because best depends entirely on which dimension you’re optimizing for, and production systems must make explicit trade-offs.

The four core dimensions are: cost per request (driven by token pricing and infrastructure), response quality (accuracy, coherence, task completion), latency (time to first token and total response time), and reliability/consistency (uptime, response stability, safety adherence). Most teams discover that optimizing aggressively for one dimension degrades others.

The following subsections break down each trade-off with concrete examples and numbers.

Cost vs quality

Token pricing differs substantially across providers. GPT-5.2 and Claude 4.5 Sonnet sit at premium price points, while Claude Haiku and Google’s Gemini Flash offer cost efficiency for simpler tasks. Gemini 3 Pro falls somewhere in between, and open models can eliminate per-token costs entirely if you’re willing to manage infrastructure.

Consider a concrete example. Your application generates 1 million responses per month, averaging 1,000 tokens per response, meaning 1 billion output tokens monthly. At $15 per million tokens (typical for frontier models), you’re spending $15,000/month on inference alone. A smaller model at $1 per million tokens drops that to $1,000/month. But if the cheaper model’s quality forces 10% of responses into manual review at $5 per review, you’ve added $500,000 in labor costs.

The “cheapest model” is often a false economy if it increases support load, error correction, or user churn downstream. Rather than picking by price alone, plot quality versus cost across candidate models to identify a Pareto front, the set of models where you cannot improve one dimension without sacrificing another.

Latency and user experience

Typical latency ranges vary dramatically. Lightweight models and optimized endpoints deliver 300-900ms response times, while larger models can take 1-5+ seconds for complex requests. Streaming output affects perceived speed; users tolerate longer total generation time when they see tokens appearing immediately.

Latency constraints differ by context. A customer support copilot where agents wait for suggestions has different requirements than a back-of-house batch job processing thousands of documents overnight. For the copilot, each additional second of latency drives agent frustration and reduces adoption. Users abandon tools that feel slow, regardless of how accurate they are.

Vendor documentation often reports single-request averages under ideal conditions. However, a model that performs well in isolation might degrade significantly when handling your actual request volume.

Reliability and consistency

Reliability encompasses multiple dimensions: availability (uptime and rate limits), response stability (low variance for identical prompts), and safety/compliance adherence. Different models exhibit different propensities for hallucinations and different abilities to follow complex instructions.

Real events illustrate this risk. Regional outages and rate-limit tightening by major providers in 2025 disrupted production systems. Teams without fallback strategies faced hours of downtime. Model drift and silent updates add another layer: the same prompt may produce different behaviour after a vendor revision, breaking workflows or invalidating your evaluations.

Concrete mitigations include multi-model fallback (route to a secondary provider when primary fails), circuit breakers (stop sending requests to a degraded endpoint), and ongoing regression evaluation runs. For example, you might run nightly experiments against a fixed test set to catch behavioural changes before they impact users.

Why LLM benchmarks often fail in real production

Public benchmarks like MMLU, GSM8K, HumanEval, and HELM are invaluable for research, but weak as sole decision criteria for production LLM selection. They provide a common yardstick for comparing models across the industry, yet they systematically fail to capture what matters for your specific application.

The limitations are concrete. First, benchmarks lack domain specificity; performance on general knowledge questions tells you little about medical triage or legal document analysis. Specialized models often perform better in specific areas than general models. Second, test distributions become outdated as language and domains evolve. Third, most LLMs on benchmark leaderboards are English-heavy, underrepresenting performance on other languages your users might need. Fourth, benchmarks ignore cost and latency dimensions entirely.

Analyzing your own text data is crucial to identify suitable use cases for language models and automation. Consider an example: a model scores slightly higher on MMLU but underperforms dramatically on your internal legal QA dataset because legal reasoning involves edge cases and domain-specific terminology that general benchmarks don’t cover. The benchmark leader isn’t the right model for your use case.

Vendors selectively optimize for common benchmarks, creating “teaching to the test” effects that don’t generalize to real customer prompts. When a new benchmark gains popularity, model training pipelines adapt to maximize scores on that specific distribution.

At Trismik, we treat public benchmarks as a first filter only. They help narrow the field from dozens of models to a focused shortlist of viable options. The final selection, however, comes from custom experiments that reflect your team’s real traffic, risk profile, and success criteria.

Why evaluating LLMs on your own data changes everything

The most trustworthy signal for LLM selection is evaluation on your own data, with your own definitions of success and failure. Generic benchmarks measure performance on someone else’s distribution. Your production system serves your users, with your specific input patterns and your specific quality requirements. Selecting models capable of producing human-like text is crucial, as natural, coherent responses enhance user experience and trust.

Using historical chat logs, support tickets, internal documents, or code repositories creates a distribution that matches real production use. You’re testing how models behave on the actual inputs they’ll receive, including the messy, ambiguous, and domain-specific queries that benchmarks sanitize away.

Task-specific metrics matter more than aggregate scores. For classification, you might care about exact-match accuracy. For summarisation, BLEU or ROUGE capture lexical overlap, though semantic similarity often matters more. For content creation workflows, human preference scores or accept/reject labels from domain experts provide the strongest ground truth, while LLM-as-a-Judge (LLMaJ) approaches can offer scalable, consistent proxy judgments when carefully calibrated. Different tasks weight different metrics, and it is important to see how each model performs on the specific tasks relevant to your use case, as most LLMs perform unevenly across these dimensions.

Risk metrics deserve equal attention: hallucination rate on factual queries, harmful content rate, bias across demographic slices. These vary between candidate models and matter enormously for applications handling sensitive data or making decisions with real consequences.

Here’s a high-level example: a support team wants to evaluate models for ticket classification. They export 500 historical tickets with human-assigned categories. These become the evaluation dataset. Models are tested on classification accuracy, time-to-response, and hallucination rate (does the model invent ticket details?). The model that wins on benchmarks might not win on this real-world task.

How to choose a Large Language Model in practice

In real teams, LLM selection rarely follows a perfect experimental design. It usually starts with a specific product problem, a short list of candidate models, and a growing pile of prompts, examples, and edge cases.

A practical workflow looks less like a formal benchmark, and more like a structured comparison process you can repeat as models and requirements change.

The goal is not to find “the best LLM”, but to find the best model for your task, your data, and your constraints.

This section outlines a practical, step-by-step framework ML and product teams can follow to compare models quickly and make informed decisions. The same process applies whether you’re selecting a model for a new feature or re-evaluating your current choice.

Define the task and success criteria

Start by clearly describing the task the model must perform. Keep this focused on real product behaviour, not abstract capabilities.

A short task definition should cover:

- Input: what the model receives

- Output: what a correct response looks like

- Constraints: latency, format, safety or business rules

- Failure modes: what would break the user experience

For example, a code review assistant might require structured comments with line references, no hallucinated APIs, and low false positives on stylistic issues.

Next, decide how you will judge success. Depending on the task, this might include accuracy, LLM-as-a-Judge, human preference, formatting compliance, latency, cost, or downstream product metrics.

Finally, assemble a small, realistic evaluation set (often 100–300 examples) from real data. Where possible, include reference outputs or human judgements. This dataset becomes the shared baseline for all comparisons.

Test across multiple dimensions

Run each model on the same dataset using consistent prompts and settings.

At a minimum, assess:

- Output quality and usefulness

- Hallucination or factual error rate

- Safety or policy compliance

- Latency and cost

Use a mix of automated checks (format validation, exact matches) and human or rubric-based review for subjective quality.

To reduce noise, avoid judging models from a handful of manual prompts. Instead, test enough examples to expose patterns, and log model version, parameters, dataset version, and run time so results remain reproducible.

Tools such as Trismik’s QuickCompare can help organise these runs and keep comparisons consistent, but the core principle is discipline: same data, same task, same evaluation logic.

Compare models on your own data

Compare models side by side on the same evaluation set.

Typical signals include:

- Accuracy or win-rate versus a baseline

- Average human or rubric score

- Hallucination or failure counts

- Cost and latency per request

Visual summaries often reveal trade-offs alongside data from raw tables, such as quality versus cost or error rate comparisons.

Where possible, validate results with limited production exposure. Feature flags or controlled A/B tests help confirm whether offline evaluation aligns with real user behaviour.

Re-evaluate when models change

Model versions, pricing, and behaviour change frequently. A decision made months ago may no longer be optimal or even safe.

Keep your dataset, prompts, and evaluation logic versioned so you can rerun comparisons when:

- A model version updates

- A new candidate model appears

- Your product requirements change

This turns model selection from a one-time decision into a lightweight, repeatable process that protects production quality over time.

QuickCompare can automate much of this re-execution and comparison, but the key advantage is the workflow itself: consistent, task-specific, and repeatable evaluation.

Choosing between GPT, Claude, Gemini, and other models

GPT, Claude, Gemini, and strong open models like Llama 4 and Mistral Large 3 each have specific strengths. No single model dominates across all tasks, and selecting the right LLM depends on your specific requirements.

A concise overview of typical use-case fit:

| Model Family | Typical Strengths |

|---|---|

| GPT (OpenAI) | Broad ecosystem, extensive tool integrations, strong reasoning |

| Claude (Anthropic) | Long-context reasoning, document-heavy analysis, safety focus |

| Gemini (Google) | Google-native integrations, multimodal tasks, competitive pricing |

| Open models (Llama, Mistral) | Strict data control, custom fine tuning, no per-token costs |

Selection should be task-by-task. A single product might use one model for retrieval-augmented generation, another for draft composition, a third for classification, and a fourth for safety filtering. Proprietary models offer convenience and cutting-edge performance; open models offer control and cost efficiency at scale.

Avoid vendor lock-in by designing an abstraction layer that allows swapping models without rewriting application logic. This isn’t just about hedging risk; it enables you to move quickly when a better option emerges or a provider changes pricing.

Common mistakes teams make when selecting LLMs

Based on patterns we see at Trismik when working with ML and product teams, here are the most common pitfalls in LLM selection:

- Relying only on public benchmarks and vendor leaderboards. Benchmark performance on MMLU or HumanEval tells you about general capabilities, not about your specific task distribution.

- Judging models from a handful of internal “demo prompts” instead of a structured evaluation set. Ten cherry-picked examples don’t provide statistical confidence about real-world performance.

- Ignoring latency, cost drift, and rate limits until late in implementation. Discovering that your chosen model adds 3 seconds of latency after you’ve built the feature is expensive.

- Not testing safety and bias on their own user data and languages. Most benchmarks are English-centric; your users might not be.

- Treating model selection as a one-time project, not an ongoing process. Models update, deprecate, and change behaviour; your selection needs to evolve.

- Failing to log experiment settings, making results unreproducible. When you can’t reproduce an evaluation, you can’t trust it.

- Over-indexing on a single provider without a fallback plan. Provider outages happen; teams without alternatives experience downtime.

Each mistake is avoidable with lightweight process and appropriate tooling. The cost of doing evaluation and model selection properly is far lower than the cost of deploying the wrong model.

A more defensible way to make LLM decisions

Moving from “vibes-based” decisions to an experiment-driven process creates decisions that stand up to internal review and external audits. When someone asks “why did you choose this model?”, you can point to structured experiments with reproducible results.

The core loop is straightforward: define tasks and success criteria, run controlled experiments on representative data, ship limited rollouts to validate in production, collect metrics, and feed results back into the next experiment. This mirrors familiar engineering concepts: versioning, experiment tracking, regression tests, and hypothesis-driven changes.

This process is especially important for high-risk areas. Financial advice, healthcare triage, legal drafting, HR screening, and safety-critical workflows all demand defensible model choices. Regulators, compliance teams, and customers increasingly expect evidence that AI systems were evaluated rigorously.

Consider a fintech product team building an LLM-powered analyst assistant. They need to demonstrate to regulators that their model was selected based on accuracy on financial reasoning tasks, low hallucination rates on factual queries, and appropriate handling of various factors including market conditions and risk disclosures. An experiment-driven process with logged results provides that evidence.

Summary: choosing the right LLM is a process, not a one-time decision

Model selection is multi-dimensional. Quality, cost, latency, and risk all matter, and optimizing for one often sacrifices another. The right large language model for your use case depends on your specific task type, data distribution, and operational constraints.

Public benchmarks are a starting point, not an answer. They help narrow the field but cannot substitute for evaluation on your own data with your own success metrics. Task-specific testing reveals how models actually perform on the inputs your production system will receive.

Continuous re-evaluation is required as models and workloads change. Vendors update models, deprecate versions, and shift pricing. Your data distribution evolves as users change behaviour. The teams that succeed treat LLMs like any other critical infrastructure: monitored, tested, and improved continuously.

“How to choose an LLM” is really about putting an evaluation process in place, not finding a single permanent winner.

Call to action: compare Large Language Models on your own data

The most valuable thing you can do today is move beyond generic benchmarks and start running structured model comparisons on your own datasets and tasks. Real data from your production environment or historical logs provides insights that no public leaderboard can match.

Trismik’s QuickCompare is a practical, engineering-focused tool that lets teams connect their own data, run side-by-side experiments across GPT, Claude, Gemini, and a wide range of other proprietary and open-weight models, and analyse trade-offs across quality, cost, latency, and safety. It is designed for ML and product teams who want reproducible, science-grade evaluations without building a full experimentation stack themselves.

Run a first, small evaluation with 200-500 examples to pressure-test your current model choice before your next major release. You’ll likely discover something surprising about how different models perform on your specific use case, and that insight is worth more than any benchmark score.